Published in Freedom Network News April-June 2001

Sarah Fitz-Claridge, 2001

When a friend invited me to join a group of young people travelling to Quebec City to demonstrate at the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas) summit, I accepted readily. If thousands of protectionists were going to be protesting against trade, someone should be there to make the case in favour of it. We would be protesting that the FTAA may be a good start but it doesn’t go nearly far enough: the entire world should be a free trade area. And anyway, it sounded like fun!

I began to have doubts when these young libertarians began earnestly explaining what I’d need to know about things like: Tear gas. The risk of getting beaten up by angry socialists. How to avoid being arrested. What to expect by way of police brutality. I consider myself a fun-loving person but I’d rather get my kicks metaphorically than literally. Tear gas is painful and, I was told, carcinogenic. And generally speaking I prefer not to throw myself up against the sharp end of law enforcement. I began to feel that this might be something I’d rather watch on television than experience first hand. My reservations were only increased when a friend helpfully sent me a copy of some advice for demonstrators, posted on the internet by one of the anti-FTAA groups.

Reading between the lines, I could tell that the writer’s expectations of this gathering differed somewhat from my own. I had envisioned an enjoyable, relaxed picnic in the sun, enlivened by vigorous debate. He spoke of thermal underwear to stave off hypothermia during three days and nights out on the streets. Body padding. Boots with steel toe caps, in case one found oneself “playing hopscotch with a clumsy policeman.” He pointed out that there might be no way of getting to a toilet and that anyone too shy to pee in the streets should wear a catheter. “Don’t worry,” one of my friends assured me, “they will give warnings before they arrest or tear gas people. It won’t be like Seattle.”

A friend living in Quebec City advised us to bring plenty of food, “because the entire city is boarded up and you might not be able to buy any here. It’s like a ghost town here—everyone’s left or leaving, and the police have erected road blocks at all the main points of entry. You might get turned away.” So we might be driving for ten hours only to be turned away when we arrived? “Let me get this straight,” I said, “everyone in Quebec City is boarding up their homes and businesses and leaving for the duration, but we are going there?”

“There’s going to be nothing to eat and drink, and we’re going to be rubbing shoulders with a bunch of men who haven’t washed for a week and are using the streets as a toilet, and who might not take too kindly to our counter protest. And you’re still thinking of going?” I wondered if my friends have masochistic tendencies. I mentioned that I have an extremely strong preference not to get arrested. They called this “a finite risk,” and advised me to “avoid the front line.” I am not the sort of person who would enjoy going anywhere near a front line, let alone strolling about in the front line of an enemy army. I discovered that my health insurance wouldn’t cover me: it has exclusions for “civil commotion” and “provoking assault.” I didn’t fancy my chances at persuading the insurance company to pay in the event that I was beaten to a bloody pulp by someone who was enraged by my “Stop Trade, Starve Kids” placard. Anyway, I want to live for ever, so coming to a sticky end now would be a sub-optimal outcome. I decided not to go.

But then, inexplicably, the evening before they were due to set off, I changed my mind. I told myself that I would keep a low profile, avoid trouble, and stay well away from the action. If things got hairy, I could always leave, and besides, I had always wanted to visit Montreal, which was en route.

I hurriedly packed a small bag with everything I thought necessary, which was not much. I considered taking a fur jacket. “Unwise!” my friend snapped. But I had heard that in Canada, there is no militant anti-fur activism like there is in England, because Native people wear fur. “Yes, Native people, not you,” my friend explained exasperatedly. “I thought you wanted to avoid trouble!” Later, in Quebec City, we saw graffiti saying that the FTAA violates “human and animal rights,” so I was relieved that I had left my fur behind, even though it was so cold at night that sleeping fully clothed was not enough to keep me warm—and I was sleeping in a hostel, not out on the streets like many of the anti-FTAA demonstrators.

When we arrived, we had difficulty finding our hostel because of the now famous “perimeter.” To ensure that the FTAA talks could take place without interference or violence, a vast concrete and metal barricade had been erected to seal off a sizeable chunk of the city. This was punctuated by the occasional gate to allow approved persons in and out, and there were police guarding its entire length. Every street we tried to drive down seemed to be blocked. It looked like the set of a big-budget Cold War film. Eventually, we gave up and parked outside the city centre, walking back into the old town to our hostel. There was a Kafkaesque disquiet in the air. When I dumped a bag of rubbish in a bin, a security guard immediately rushed up and warily checked its contents.

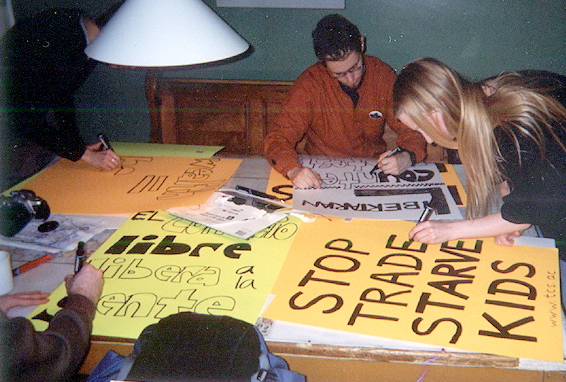

In the morning, we met some other libertarian counter demonstrators, who had come from all over the US and Canada. I was the sole British representative. We started making placards. There was quite a lot of tactical disagreement about these: were we against the FTAA or for it? Should we be conciliatory, or contentious? Eventually, we had created enough placards to please everyone. Some were straightforward (Free trade now!), others were informative (Free trade frees people!, Trade saves lives!). Some were for amusement, for the libertarians who didn’t want to offend the opposition (Free love, free trade!, and Free trade for Coca farmers) and others took the moral high ground (Pro-choice on trade, Free trade IS fair trade!, Profits not poverty! And my own Stop Trade, Starve Kids). We were worried that we might fall foul of Quebec’s language laws, so we tried to make a few in French too:

The route from our hostel took us past the local McDonalds. If we had felt like a Big Mac before the big event, we’d have been disappointed, because it was closed. Not just closed, but invisible. At a previous demonstration in England, anti-capitalist protestors had trashed a McDonalds, so the management of this one were taking no chances. They had had it completely boarded up, so that only those who already knew would realise what the building was. Nevertheless, someone had given it a sinister yellow “M”, like the mark of doom. When we passed by later, others had added in angry red, “Pigs”, and in black, “Murder.”

By now there were quite a few people around, including the media, who filmed us holding our placards in front of the McDonalds. One of us made an impassioned and very amusing speech. “I’m hungry! I want a hamburger! But can I get one? No! Because McDonalds has been bullied into closing by the anti-capitalist protestors. Your child wants a hamburger? These people are here to stop you buying her one. They are here to make her go hungry just like the Third World children. They talk about freedom but am I free to buy a hamburger here today? Is McDonalds free to trade in peace? No! Leave McDonalds alone! Free trade for McDonalds! Hands off our hamburgers!”

We spent a very enjoyable afternoon in the sun near the perimeter giving interviews to journalists and TV crews and having heated but generally good-natured arguments with people who were attracted—if “attracted” is the right word—by the free trade message of our placards. I explained that trade restrictions hurt people. We are all appalled by the terrible working conditions offered to many people in developing countries, and want to see the end of such terrible poverty. But restricting trade only makes matters worse. It might make economic sense for Western companies to hire poorly-skilled workers in far-off, risky places—if the cost of hiring them is low. But the more that cost is artificially raised by government regulations imposing minimum wages and conditions, the cheaper it becomes to hire expensive, highly-skilled Western labour instead. Where does that leave those people who would otherwise have had jobs? For them, the alternative to working in poor conditions for little pay is not, as the anti-FTAA protestors think, working in good conditions for good pay, but not working at all, which means still greater poverty and, for some of them, death. Who are we to say to people who want work, “Sorry, these conditions are unacceptable to us. We prefer you to starve instead.” That is what those fine-sounding protest slogans about “ending exploitation” really mean.

Some of the libertarians quoted statistics showing that countries which have reduced trade barriers have become more wealthy, while those which have increased restrictions have declined. “No country which has closed its borders to trade has flourished,” argued one. “Why is it that some countries have no natural resources yet are rich, while others have plenty of natural resources but are poor?” I asked. “Western exploitation!” was the riposte. “No, it’s because the people there have bad ideas, few skills, are under tyrannical governments, and do not have capitalist institutions,” I countered. “If they are to climb out of their poverty, they have to create wealth! How are they to become wealthy without trade? By rubbing a magic lamp?” “No,” I was told, “what we need is the redistribution of wealth. Let greedy capitalist pigs pay. They can afford it.” At least we were in agreement that what creates wealth is capitalist enterprise.

They didn’t take it very well. An angry woman shouted that I can’t have even visited the third world (not true actually) or I’d know that what I was saying was “bullshit,” and that I should go and live there before I “spout such crap.” A large crowd gathered to see what all the commotion was about. I replied that I wouldn’t dream of going to live under a corrupt anti-capitalist dictatorship. She retorted that the only reason the third world is in the state it is in is because of Western pillaging and that before Western imperialists arrived, third world people lived happily as hunter-gatherers. (They didn’t actually.) “So you think the people in the third world should become hunter-gatherers, do you?” “Yes,” she replied, “It’s a much more natural lifestyle. Hunter-gatherers only have to work a few hours a day! Compare that with Western work hours!” “In that case,” I enquired, “why don’t you have the courage of your convictions? Why stay living in the West if you think it is so bad? Why don’t you go and become a hunter-gatherer?”

“Why don’t you?” she challenged, unexpectedly.

“Because I think the West is better. I think Western values are right. Unlike you, I don’t think hunter-gathering is an attractive lifestyle. If hunter-gathering is “natural”, then pain and sickness are natural too. What do hunter-gatherers do when they need life-saving medicine or operations?”

Medical care and all other basic necessities of life should be free, others asserted. I asked: “Where are these things going to come from? Who is going to pay for them? Whom do you want to enslave to provide them?” “That’s what taxation’s for,” someone sneered.

One man said that water is provided free by nature and should remain free. I pointed out that he is already free to collect his own rain water, but that the local supermarket might not appreciate it if he thinks they should supply him with free Evian. He scoffed that rain water is no good because it’s contaminated by industrial wastes, and so is the whole water supply. I felt like congratulating him for still being alive under these difficult conditions, but said only that the solution to such problems is the institution of private property. If someone owned the river into which Evil Company X was pouring toxic waste, that Someone could sue the company for damages.

A woman was outraged by the fact that we used the phrase “pro-choice” in our “Pro-Choice on Trade” banner. I explained that we believe in freedom as opposed to coercion, and that we don’t draw the line at economic freedom as anti-capitalists do. I put it to her that just as she believes that it is not right for a government or anyone else to deny a woman the right to choose, it is likewise not right for a government or anyone else to deny people the right to trade amongst themselves. She became intrigued and asked more questions about libertarian ideas. By the end of our conversation she was practically offering to carry one of our placards.

Several people contended that free trade is all very well in theory, but that in practice it is a disaster. When asked for examples, they couldn’t give any, but they argued that whilst it is fine for countries that are all at the same level of economic development, “trading with countries which are poorer leaves their people open to exploitation.” (So the US would not be allowed to trade at all? Where would I get my next Apple computer?) I asked how not being allowed to work would help a third world person out of poverty. They asked whether I am aware that third world countries use child labour. I replied, “Yes, so what will you say to the orphan in the third world who wants to work, whom you are condemning to death by prohibiting child labour?”

Some of those who argued with us were more friendly than others. Some listened to what we had to say; most merely jeered or heckled or branded us “ignorant” without stopping to listen to a single argument. One, though, said that he was glad to see us there even though he disagreed with our position. Another said that he had listened to many people that day, and that he couldn’t help noticing that the quality of our discussions was far higher than that of any others. A professor of business and economics at the local college stopped to chat, surprised to see us there, and wished us well.

All in all, the debates that afternoon were both enjoyable and non-violent, and these were followed by a short rally nearby which was also peaceful. After the rally, the protesters left, and we sat on the grass in the sun, eating our meal-replacement bars and drinking water. We chatted and argued, and regaled one another with anecdotes about the conversations we had had. “You are one controversial lady,” chuckled one of our number, to me. Apparently, my style of argument had been rather more confrontational than usual. “Yes, and I was the one who didn’t want to come!” I reminded them.

I have always found it difficult not to say what I think. But there is more to it than that. To be apologetic about these ideas in particular, it seems to me, is wrong. It conveys the impression that we ourselves suspect that the opposition may be right in thinking us evil. Some of the protestors at Quebec City had clearly never met anyone who expressed to their face the opinion that capitalism is morally right. Isn’t that astonishing? These people who are making a career out of opposing the fundamental values of our society had never in their lives encountered a single person prepared to defend those values.

Those of us who were stating our moral and philosophical views were giving these people, for the first time, the information that there is a genuine disagreement about morality here. Had we just stuck to utilitarian or pragmatic arguments, as some of my libertarian friends thought we should have, we would have failed to convey that fact. “But we’ll get a lot more positive interest if we keep quiet about some of the ideas non-libertarians find unpalatable,” argued one. “Well yes, but in that case,” I replied, “why not go the whole hog and spout only anti-capitalist platitudes? Then we’d get lots of support, wouldn’t we?”

They seemed puzzled. I explained: “I’m not suggesting that one shouldn’t be civil and friendly. I’m saying that instead of trying to lure people, unknowing, onto the path we have secretly decided would be best for them, we should simply state the truth as we see it, honestly—the unvarnished truth—and allow them to make up their own minds. It is not right to poke around in other people’s minds and to try to manipulate them into what could only be the semblance of agreement. And how is toning down the truth going to help? How is telling people not our actual ideas but instead, half-truths and lies, going to persuade them of our actual ideas? It isn’t. And people are entitled to be told the truth about morality. That is, itself, a moral issue.” I wondered why there were fewer of us present when I finished my helpful discourse than there had been when we sat down.

After our relaxing break on the grass, quite suddenly, everything changed. The protesters were back, marching on the perimeter, and this time, they were in distinct groups, each with a different colour scheme like the soldiers they were. The first groups to arrive were non-violent, so we stood by the side of the road shouting our slogans and holding our placards aloft to give them all a good view. Then the atmosphere turned ugly. After the anti-capitalists in red came the scary people—the black-clad, padded, gas-mask-wearing violent revolutionaries. They reminded me of an advancing army of Borg drones, only more mindless and less disciplined. One of them strongly advised us to: “Shut up and go home, capitalist pigs!” Clearly not everyone there shared our belief in freedom of speech. Another spat on one of our people and tried to tear up his placard. Others came over to hurl abuse at us. But only abuse. So far.

By then, only two of us were still holding up our placards: I, and the chap who had called me “controversial” earlier. He had me in stitches, teasing the increasingly angry revolutionaries by shouting to them, “Let’s hear it for free trade everybody! Revolutionaries for free trade! Let’s hear it! I say ‘free’, you say ‘trade’. FREE!”

“For God’s sake take down your placards,” implored someone. “Don’t you know who these people are? Do you want to get us beaten up?” It felt galling to let ourselves be intimidated, but when I noticed groups of them whispering and pointing at us in a sinister way, I meekly took down my placard as suggested. At that point, we all became very frightened, and decided it was time to leave. There was not a policeman to be seen anywhere. (Why can you never find a policeman when you need one?) I didn’t think we stood much chance against this menacing mob. For one thing many of them were armed with large sticks. For another, we were slightly outnumbered—by about a thousand to one.

As we made an only-slightly-hysterical dash for our lives, the first tear gas canister exploded off to our left. We were not close enough to determine its source (we later discovered that the some of the revolutionaries had themselves been armed with tear gas bombs) but we were too close for comfort, and we scurried away from the action as fast as we could manage without looking too uncool. Only to find ourselves on the very street where hundreds of armed police in full riot gear were pouring out of large vans to take control of the now very scary situation. Seeing a police officer with his firearm trained on us, following us in his sights as we passed by, I didn’t know whether to be less scared now or more. We couldn’t agree about whether to show our placards or hide them. I wanted to keep mine showing, so that they would know that we were not anti-FTAA protesters, but the others persuaded me that that the police might be French-speakers and unable to read the placards, and in any case, they might be under too much stress to notice little details like whose side we were on.

Our immediate aim became to get back to our hostel. Unfortunately, that was easier said than done. We were on entirely the wrong side of town now, and between us and our hostel there was a war going on between tens of thousands of angry protesters and a great many possibly jumpy armed police. The protesters were not just marching on the perimeter, they were uprooting paving stones and throwing them at the police guarding it. It was because of this violent turn of events—and the fact that the angry mob had managed to tear down the perimeter barricade in two places—that the police had mobilised.

Luckily, we had a local to guide us, but even he had trouble working out how to get back. Most of the streets were packed with throngs of stick-wielding protestors and riot police who were firing off rather a lot of tear gas canisters and rubber bullets in desperate attempts to regain control of the perimeter. We kept getting blocked and having to retrace our steps and go an even-longer way round. At one point, we made the mistake of going against the advice of our guide and taking what looked like a good route down a quiet street. Before we knew what was happening we found ourselves surrounded by skirmishing protesters and police, and we realised too late that we were in exactly the wrong place at the wrong time: the police were firing tear gas canisters into the very crowd now surrounding us, and I ran for my life as I coughed and spluttered, my throat and eyes burning acutely and my eyes streaming from the tear gas.

While we waited in vain for the few members of our party who had not already got lost or left us to get closer to the action, we took the precaution of standing behind a building to avoid being mown down, and discussed how we might get back to our hostel. We had no choice. Although the vicinity of the perimeter was not a safe place to be now, it was the only way.

Thus, once again, we found ourselves in a street full of armed riot police. My legs turned to jelly as I suddenly noticed a police officer holding a firearm ready to shoot. By the time we somehow made it back to our hostel, there were only three of us left. We sat in our room, rather dazed, discussing the curious fact that our group had had no cohesion, no common purpose, and no leader. Whether this is something to expect of any libertarian counter demonstration, or whether it was just these particular libertarians who were too individualistic to be interested in doing anything as a group, I don’t know. Some of them, it later transpired, had been off trying to get themselves arrested—they had decided that they would get more interest in freedom from people who were locked up.

We felt unclean. Physically unclean because we had been exposed to tear gas, which gets into one’s clothes and lingers; and psychologically unclean because we had been exposed to so many very ugly ideas, and because we had seen such rage and violence and intimidation being employed to disrupt the FTAA talks.

We had intended to attend a social function that the anti-FTAA protesters were holding, but we thought better of it when we remembered the scary thugs who had been pointing at us. We waited until they would all be safely at their function and then crept out of the hostel to the nearest fast food franchise for poutine, the provincial dish of Quebec.

The next morning, a few of us went for a walk around the perimeter. The air was still heavy with tear gas from the previous night, and I found myself coughing, my eyes burning and streaming again. There were several rows of police guarding each gate in the perimeter, and my friend treated them to a juggling show. We noticed that protestors had covered the nearby homes and shops with graffiti—like dogs spray lamp posts. Fuck democracy—our power is in the streets, read one telling slogan. Capitalist pigs, screamed another. And then there was Free trade means free trade in women’s bodies. Was the writer for or against?! We were cheered by the fantasy that it might a plea for the decriminalisation of prostitution—which would give a whole new meaning to the next slogan: Fuck the rich. One gibe made me laugh despite everything: Don’t feed the animals, it said, referring to the delegates in the conference behind the fence. And I imagined them in turn, peering out nervously through the fence at the savage beasts beyond.

In the car on the way out of the war zone, we had to open the windows, because the tear gas in our clothes was making our eyes and throats burn again. As we left Quebec City and headed for Montreal, I couldn’t help noticing bus after bus of protesters travelling in the opposite direction, towards Quebec City. I was glad that I had only been there for the warm-up day. Friday’s rehearsal had been quite enough for me. Saturday would be the real thing.

Sarah Fitz-Claridge, 2001, ‘Adventures in Quebec City: Diary of a reluctant counter demonstrator’, Freedom Network News, April-June 2001, https://fitz-claridge.com/adventures-in-quebec-city-diary-of-a-reluctant-counter-demonstrator