Some years ago, David Deutsch and I conducted a fascinating survey for Taking Children Seriously and reported the results in the paper journal, Taking Children Seriously 23. We asked: “Which of the following things are so important that children must do them even if they cannot be persuaded to, and are distressed at being forced to?” The results are both fascinating and useful for those of us striving to take our real children seriously in our real lives. Noticing and understanding the phenomenon that the survey highlights can dissolve fears and help us question our unchallenged false assumptions.

This does not only apply in the case of parents who are opposed to taking children seriously. Even those of us who thoroughly agree with the idea of taking children seriously will notice that whilst taking our children seriously seems effortless in many respects, there may be an issue here or there about which we find ourselves feeling anxious.

In my case, for example, when my first child was two years old, I felt considerable anxiety about her not wanting to hold my hand as we walked along a very busy London road, until I had a conversation with a friend of mine who despite being a firmly authoritarian parent, found my worry that it might be dangerous for a two-year-old child to be walking along a busy London road without holding her parent’s hand completely absurd—she had zero concerns about her own two-year-old not holding her hand when walking on busy London streets. On that particular issue, it was my ‘strict’ friend, not I, who was the rational one! I talked about that, and about this Taking Children Seriously survey, on this podcast.

Here is our survey, which David wrote up for the journal:

On the Taking Children Seriously List a while back, there was a most interesting discussion about bedtime and tooth-brushing. One parent who was entirely relaxed and non-coercive about bedtime nevertheless asserted that if children refuse to brush their teeth, it is ‘necessary’ to hold them down and brush their teeth forcibly. Another parent, who was defending as ‘necessary’ the practice of forcing children to go to bed against their will, had no trouble in allowing them the last word in regard to their teeth. Each of these parents was contemptuous about the other’s position, but completely unable to see reason in their own case. They were making essentially the same arguments against each other’s positions. But they did not find them convincing: on the contrary, each seemed literally unable to understand what the other was saying.

Such amazing blindness may seem puzzling. It doesn’t make sense if you have in mind the idea that parents behave as they do for the reasons they give. In fact, the causality is normally in the opposite direction: from behaviour to justifications. What happens is that parents find themselves overwhelmingly compelled to behave in a certain way, and then they unconsciously invent a plausible justification. When, under criticism, one of these justifications begins to seem inadequate, they invent another, while holding the behaviour itself inviolate. Thus the pattern of issues over which parents are prepared to distress their children depends entirely on the entrenched ‘fixed points’ in the parents’ own makeup—which in turn are caused by the patterns and accidents of their own lives, especially the style of coercion in their own childhoods.

Needless to say, few parents would recognise this description of themselves. Almost all of them believe that their particular pattern of coercion is, above all, meaningful. They believe that they are coercive only when the issue is sufficiently important, and that (borderline cases aside) it is reasonably obvious which issues are very important and which are trivial. Thus they believe that they choose the issues over which they are prepared to distress their children, using an objective criterion of importance. Where the issue is important enough, they will be coercive if necessary, where it is less important, they will not.

The conventional terminology of ‘strict’ vs. ‘lenient’ parents reflects this belief in a reasonably uncontroversial order of importance of various issues. A ‘strict’ parent is one who enforces even the less important items; a ‘lenient’ parent is one who enforces only the most important items. People differ in how strict or lenient they are, but they believe that everyone is in broad agreement on the order of importance of various issues: matters of personal safety come above matters of social convention, for instance. Obviously! That is why parents find it disconcerting when they discover that there is no consensus at all about which is which. They encounter another parent, apparently well-meaning and perfectly sane in every other respect, who is highly coercive over an ‘unimportant’ issue, but non-coercive over a ‘very important’ issue. It demonstrates to them that this scale of ‘importance’ on which they believe they are basing their decisions is neither obvious nor uncontroversial. It is not an objective source of justification for their pattern of coercion, but is simply a subjective statement of the fact that they feel an inner need to be coercive over some issues and not others.

If this is so, you would expect the situation of two parents, one of whom is coercive over issue A and not issue B and another who is coercive over issue B and not issue A, to be very common. We predicted that it would occur over every pair of issues over which children are commonly coerced. Another prediction was that although some issues very commonly give rise to coercion and others very rarely do, nevertheless the fact that someone advocates coercion over a given issue would be a very poor predictor of whether that person also advocates coercion over any other issue. In that sense you would expect people’s patterns of coercion to be haphazard, and not correlated as would presumably be the case if the various issues really could be ranked in an objective order of importance.

We decided to put these predictions to the test. We devised a questionnaire asking people to state which issues they thought were important enough to justify coercion. Then we posted the request shown below in as many relevant places on the Internet as we could think of:

Recently the folks on the Taking Children Seriously List have been discussing different definitions of ‘coercion’ in child-rearing, and the various circumstances in which it may or may not be necessary. It seems that there are remarkably many different definitions and opinions, perhaps one per parent, but one thing that virtually all parents seem to agree on is this: there are some things perhaps very few which children simply have to do (or have done to them, as the case may be) whether they like it or not.

We are conducting a survey to try to identify what this inner core of things is. We are not referring to extreme situations but only to quite ordinary ones that can be expected to arise regularly in normal family life. We have compiled a list of suggested situations. What we would like you to do, if you want to help in the survey, is to answer the following question:

Which of the following things are so important that children must do them even if they cannot be persuaded to, and are distressed at being forced to:

Not playing with fire

Receiving vaccinations

Going to school

Not telling lies

Brushing teeth

Bathing

Learning to read

Coming home on time

Not climbing a tree deemed to be dangerous

Doing chores

Wearing warm clothes in the cold

Saying please and thank you

Going to bed at bedtime

Learning to swim

Eating vegetables

Religious observance (e.g. going to church)

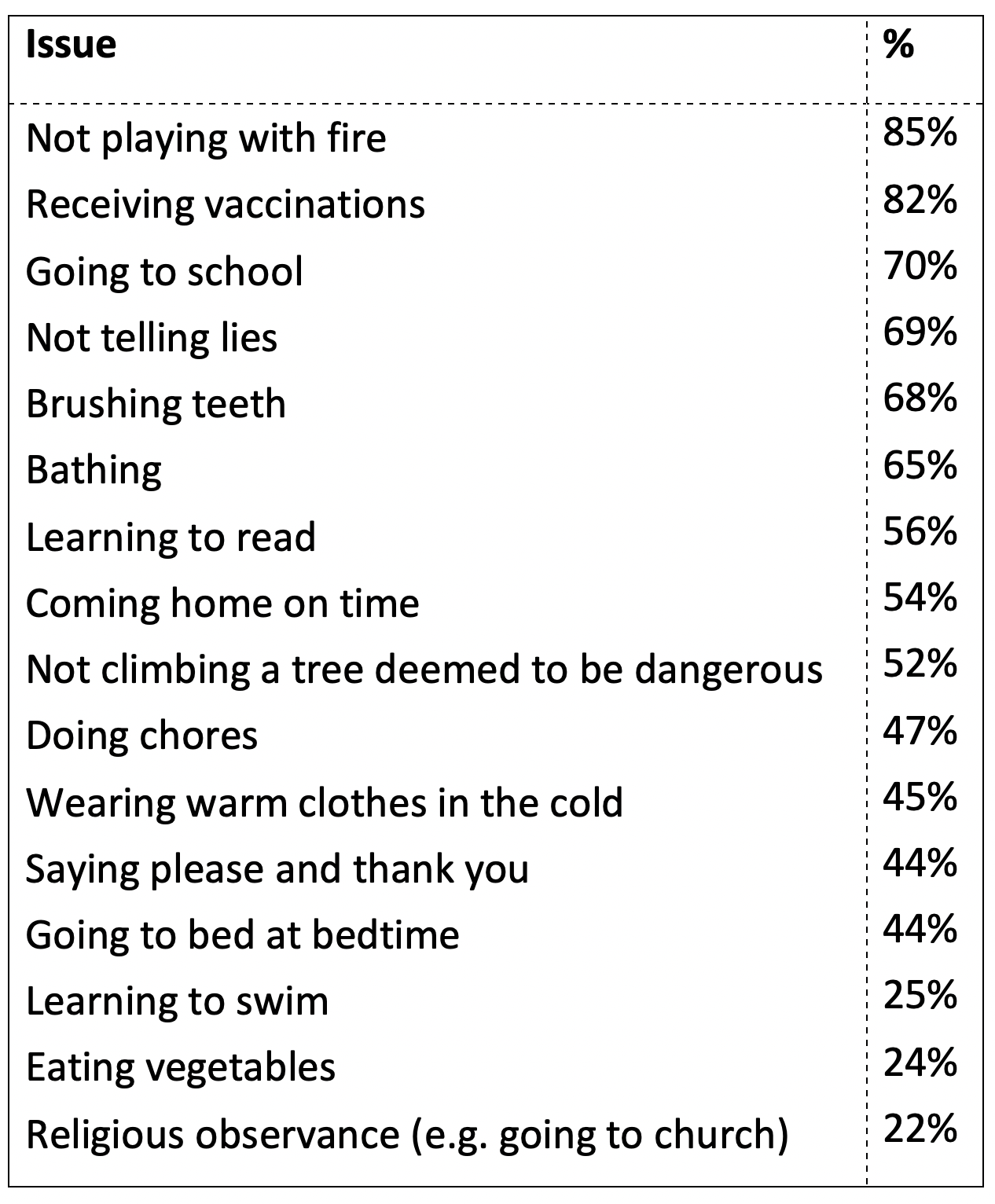

We received 318 usable replies, and the percentages of respondents who checked each issue are shown in decreasing order in the following table:

The average number of issues checked per respondent was about nine out of the sixteen. If the order of popularity of these issues reflected anything like an objective order of importance, you would expect a ‘typical’ respondent to check something like the nine most popular issues (i.e. the first nine issues in the table above). But in fact, not a single actual respondent replied in that way, and the great majority replied very differently: the average respondent answered over 5 of the 16 questions differently from that ‘typical’ response. (Even if the responses had been totally random, this average deviation would have been only 8.) 78% of the respondents gave a set of responses that no one else had given.

Now, let’s consider only the most coercive of the respondents, namely those who checked 10 or more of the 16 issues. There was not a single issue that all of them checked! This was a much more extreme corroboration of my prediction than I had been expecting. Just think what it means. Here is a group of people who all advocate coercion over vast swathes of children’s lives. Yet there is not a single issue on the list that they all agree warrants coercion. Thus, even in this very coercive group you can find someone who would prefer a child to play with fire than to be distressed, and someone who would allow a child to refuse a vaccination if it distressed him, and so on for every single issue.

Now consider the least coercive respondents, namely those who checked 5 or fewer issues. There was not a single issue that all of them left unchecked. These are all people who refuse to coerce children even in areas where the great majority of people think coercion is necessary. Yet there is not a single issue on the list which these ‘lenient’ people all agree does not warrant coercion. There are those among them who would force a distressed child to eat vegetables; there are others who would force a child to attend church against his will, and so on for every single issue.

The phenomenon that started this whole investigation off can indeed be observed for every pair of issues, not just tooth-brushing and bedtime. That is, for every pair of issues A and B in the list, there were respondents who thought that A warrants coercion but B does not, and others who thought that B warrants coercion and A does not.

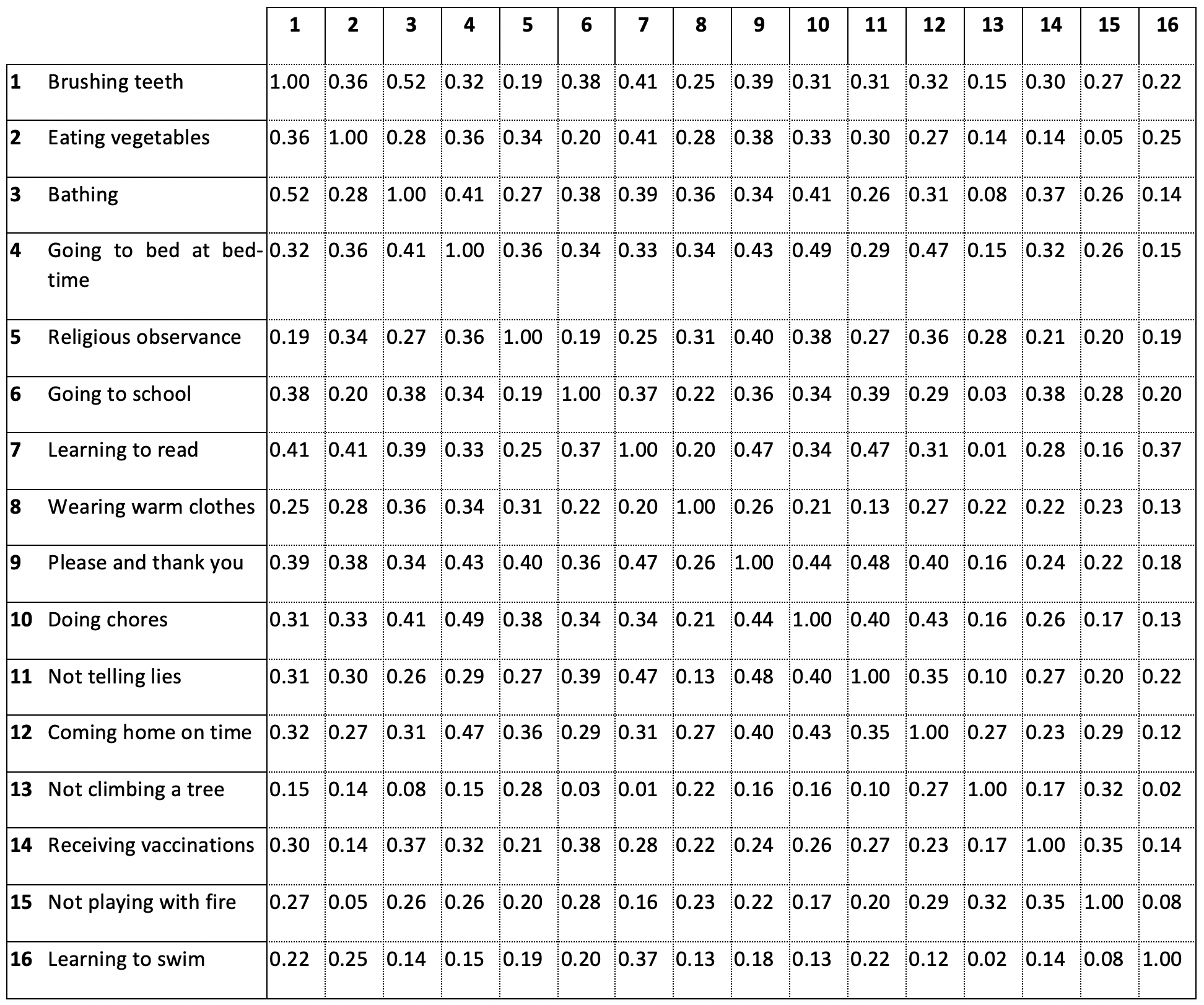

As the table above shows, there was a large majority—up to 70%—in favour of coercion over some of the issues. Nevertheless, as predicted, favouring coercion over any one issue is not a good predictor of favouring coercion over any other issue, even an issue that the majority considers more important. Responses to different issues were only weakly correlated. The correlations are shown below. (A correlation coefficient of 1 between two issues would indicate perfect correlation, i.e. that everyone who checked either of the issues also checked the other one. A correlation coefficient of 1 would indicate perfect anti-correlation, i.e. that no one who checked either of the issues also checked the other one. A correlation coefficient of zero would indicate that checking either of the issues is no guide to whether one will check the other one.) The highest correlation coefficient between any two issues was 0.52 and the lowest was 0.01.

We did not ask for further information from the respondents, but about half of them made comments in addition to checking the relevant issues. Many of these comments gave reasons why the respondent considered some issues and not others to be important enough to warrant distressing a child. The most common criterion given was that matters of ‘health’ and/or ‘safety’ were the only ones to warrant coercion. But although many respondents agreed on that criterion, there was virtually no agreement about which set of issues meet the criterion—in fact, as indicated above, the great majority gave a set of responses that no one else gave.

One respondent—apparently not a lunatic but an academic with delusions of grandeur—asked us angrily whether we had ‘received any institutional approval to conduct this study with human participants.‘ This weird complaint does not deserve a reply but it does prompt us to say a few words about the scientific status of this whole exercise. This was not a survey to find out what proportion of the population favours coercing children over the various issues. As such, it would have been fatally flawed by the non-randomness of the sample. The purpose—which was spectacularly achieved—was to demonstrate, by finding specific examples, that the phenomenon we had noticed on the Taking Children Seriously List was not an isolated one. The fact that so many of the hundreds of people who chose to reply to the questionnaire believe that so many of the others have got their priorities the wrong way round is very hard to explain in the conventional terms of ‘strict’ vs. ‘lenient’ enforcement of a larger or smaller core of objectively important things. Most of us can see quite easily the irrationality of many other people’s justifications for coercing children. But it is in the nature of irrationality that we cannot see our own.

This survey first appeared in Taking Children Seriously 23, ISSN 1351-5381, in 1997, as ‘Conflicting Certainties’, by David Deutsch, pp. 11-15, https://fitz-claridge.com/the-taking-children-seriously-survey/